|

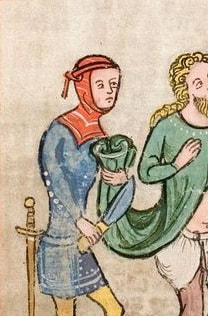

Fashion evolved fast during the 14th Century - likely faster than in any other century prior. In a 100-year span, men's tunics went from long, nearly ankle-length "super-tunics" which pulled over the head, to hip-hugging, buttoning doublets to which the hose (which also underwent drastic changes) pointed directly to, rather than a separate garment underneath. Artwork seems to show the most drastic jumps took place immediately during the post-Plague years, leading many to speculate that these leaps may have been directly influenced by individuals' experiences during The Plague. One such theory is the fit of clothing changed from loose, flowing tunics which were only semi-fitted in the chest, shoulders, and sleeve areas, and covered the linen braies and tightly-fitting wool hose almost entirely, to very tightly-fitted buttoning garments by the middle of the century. These coats, referred to today commonly as "Cottes" or "Cotehardies", both are which are likely French in origin, though names for such garments seem to have ranged greatly during the times in which they were worn, often either buttoned halfway or all the way, with buttoning sleeves (usually from elbow to wrist), and put extreme emphasis on the wearer's curves and natural body shape. It has been speculated that this extreme fittedness of these Cottes was to show the men who wore them's athletic, healthy build, and thus letting everyone know he was not a product of The Plague, which caused a high degree of unhealthiness and death to so many. During this period, a man's health was seen as his status symbol, and what better way for healthy - usually young - men to show off this status than with fitted clothing - a trend which still carries on in some form of fashion even today. This jump in fashion was not without its criticism, however, and many contemporary chroniclers were noted as having seen this fashion as "grotesque" and "ungodly". These men, who had spent their entire lives in modest, unrevealing tunics were now exposed to young men wearing clothing which showed their every curve and shape - surely the work of the Devil in pious 14th Century eyes. However, despite all the push-back, the fashion stuck, and soon evolved into even more extreme forms of fashion. In this article, we will look at one of the earlier iterations of a true 14th Century 'Cotehardie'. This particular fashion was lifted from an illustration in the "Speculum Humanae" from 1360's Germany, and was brought to life in as many details as possible to recreate what an original tunic may have looked like. The story of this tunic begins with the fabric. It is likely most - if not all - of these Cottes were made from wool. While it is also likely silk ones did exist in more high-ranking iterations, for the man depicted above, who is very likely a middle-class First Estate man (or the German equivalent, rather), his tunic is nearly undoubtedly wool. Wool was not only the staple garment textile of the period, as it had been for hundreds of years, but it also offered a natural elasticity that other textiles of the time did not, which made making the highly-fitted shape of the Cotte possible. The wool used here is a woad blue 2/2 wool twill. It has a very slightly-raised nap which adds protection from the elements without adding too much weight or thickness to the garment. The Cotehardie is then to be sewn using unbleached "white" linen thread with woad blue wool yarn being used for the buttoning side edge trims and white silk being used to sew the buttonholes, but more on that in a bit. After the fabric has been selected, the patterning process was then to begin. Making this Cotte fitted in all the right places was truly a challenge, but in the end paid off. Unfortunately, I, the model, lost a considerable amount of weight between the production process and actually getting to wear it, meaning areas like the biceps and waist are not nearly as fitted as originally intended - something I am working on remedying in the near future! With that said, the tunic was originally meant to span to about mid-thigh, and be fitted all around, meaning in the chest, waist, shoulders, arms, hips, and buttocks. With this shape, and if properly fitted, it should grant the wearer the "snaky" look so desired in period artwork. This aforementioned look means that the wearer will have a slight "S" shape to their body when wearing the garment - a fashion which may seem foreign to us today, but was highly desired during the period. It has also been determined that cutting the fabric for the garment on the textile's bias means one is taking advantage of the fabric's natural diagonal stretch and so the highly-fitted wool will not hinder the wearer's movement or cause structural damage to the garment when movement is necessary. The garment was entirely sewn by-hand using a running back-stitch technique and all seam allowances were treated by folding them over and hemming them down with an overcast stitch. When done right, no internal stitching can be seen on the outside which makes the seams look very clean both inside and out. The sleeves were a particular challenge as they are not only extremely fitted (again, since my weight loss the biceps are baggier than originally intended), but feature rounded armholes and button from elbow to wrist. This means multiple fittings are needed throughout the sewing process to ensure the sleeves are fitted all around and not so tight one cannot wear them, but also not so loose as to be inaccurate for the fashion. One way to aid in the fitting of the armholes and biceps is to add a gore at the top. This triangular gore helps add room inside the sleeve while also adding a bit of extra structural integrity. It is likely armscyes were also employed in these garments underneath the arms. As stated before, the sleeves button from elbow to wrist (a total of 17 buttons per sleeve). These are hand-made from the same cloth as the garment and are sewn directly to the edge, rather than in from it as with modern garments. The buttonholes were sewn using while silk floss in the same manner as original extant examples recovered from 14th Century sites in Germany and Britain. The buttonholes are then further reinforced with a strip of linen sewn into the inside (silk also appears to have been used for this, as well), and then finally, wool yarn was tablet-woven directly into the hem for even more reinforcement. These techniques employed together ensure the tightness of the buttons will not rip or tear the garment when in motion. The front of the Cotte is constructed in an identical manner, clothing from neck to just shy of the lower hem using cloth buttons with silk-sewn buttonholes and linen and tablet-woven reinforcements. Lastly, once all these features were complete, the issue of the lower decoration was in order. Some form of decoration is very commonly-seen on both men's and women's garments of the period, often in a very diverse array of styles. In this case, the lower hem of the man's Cotte is decorated in the very common circles and dots motif, sometimes referred to as the "Limbourg Brothers" style. Many of speculated this may have been an artistic shorthand to denote the possibility of there being embroidery present without needing to actually add detailed examples, however, it is also likely this may have actually been a fashion employed during this period. Unfortunately, we have no surviving physical examples outside artwork of it, so using it on recreated garments is purely speculative. With that said, I still decided to use it, albeit, in a more simplified manner. In the original work, the Cotte appears to have a bottom row of dots, two inner rows of lines, and a top row of dots, however, I opted to simplify this down into only one row of dots (or in this case, circles) and one line. These were sewn in the same white silk floss as the buttonholes and were done in a chain-stitch embroidery technique - an entirely period technique. Once the embroidery was applied to the lower hem, the Cotte is finished!

Reproducing 14th Century garments in particular is a rather difficult endeavor given the lack of complete clothing finds from the period, meaning we must almost exclusively go off artwork and written accounts - or piece together different fragments into a single piece at best, which can lead to all sorts of issues. However, with enough research and experimentation, I do believe it is possible to recreate an at least somewhat closely-functioning garment to those worn by fashionable men during the height of High Medieval fashion!

1 Comment

SakuPaperScissorRock

1/20/2022 09:18:15 pm

Amazing research and good read thank you it has informed my costuming as well!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AboutThis page will focus on the lifestyles of those living in Medieval Europe from approximately the 11th Century through the 14th. Archives

April 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed