|

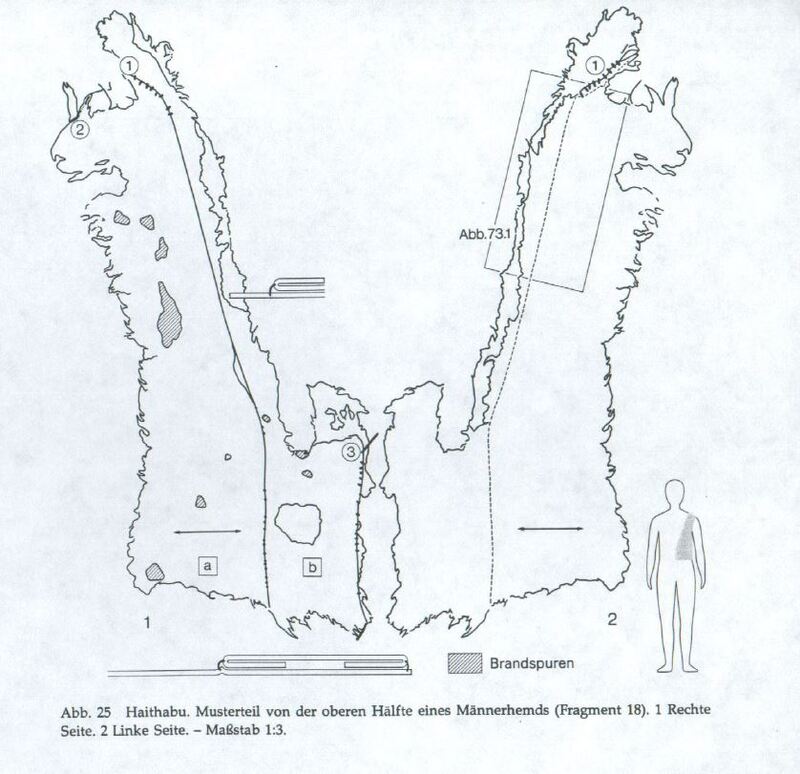

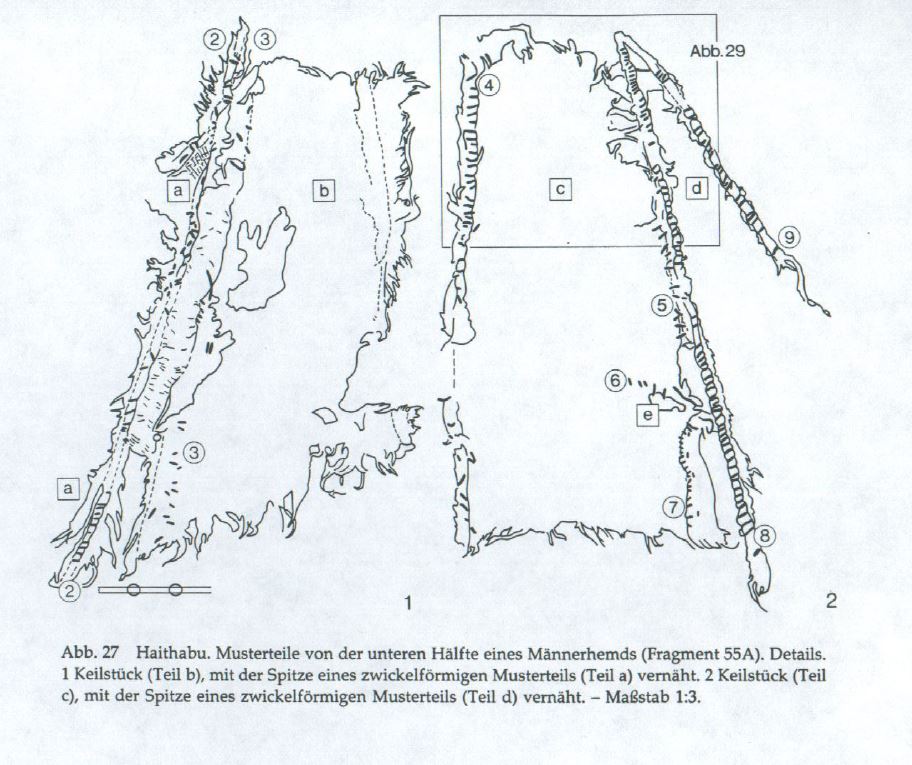

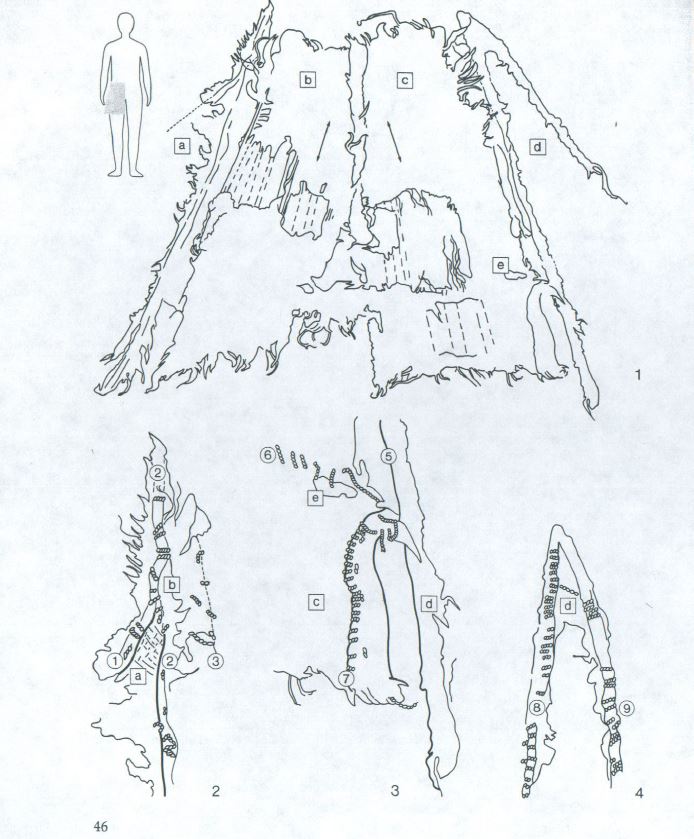

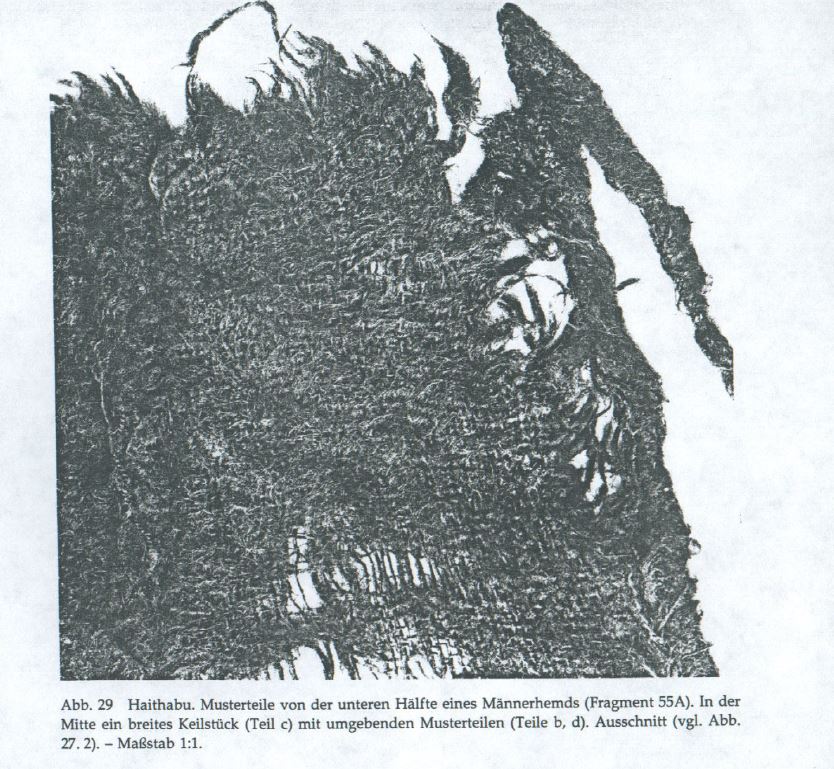

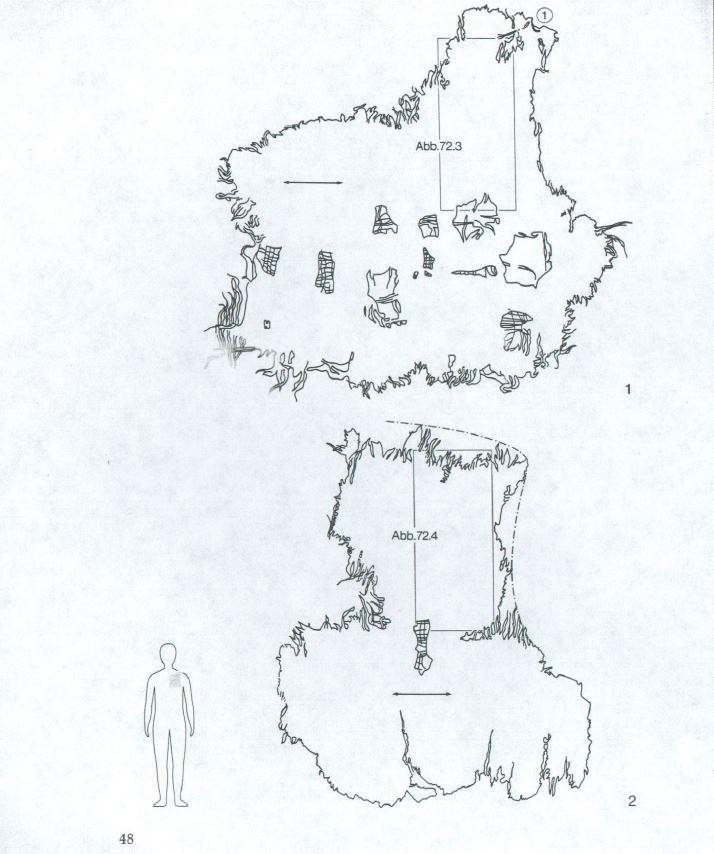

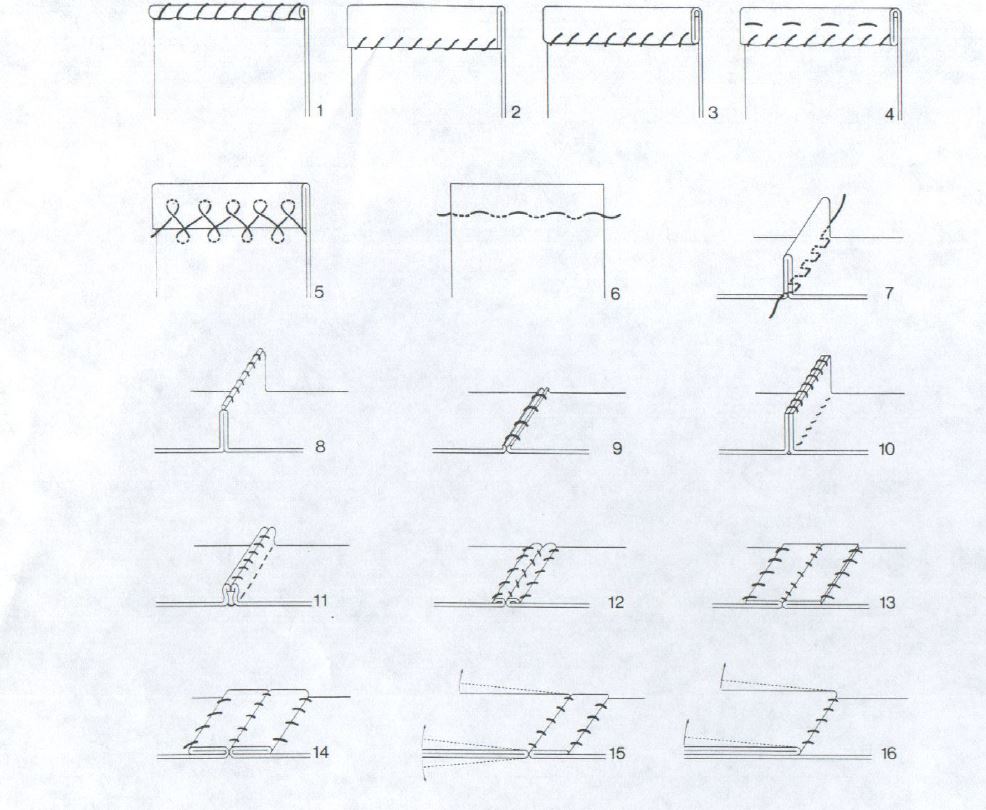

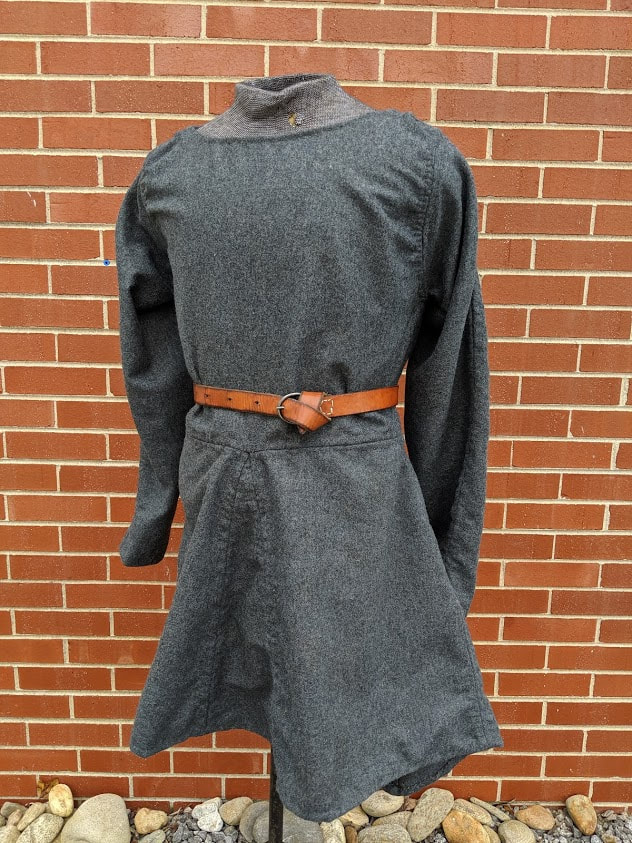

Location: Haithabu, Current-Day Germany Date: Approx. Late 10th Century Culture: Late Viking Age Danish Estimated Social Class: Possibly Middle Class Garment Type: Tunic As with any fashion in history, regional differences could be noted in Viking Age Scandinavian fashion, as well. While most modern people tend to have a general concept of what a Viking Age Scandinavian male would have looked like, most of these are generalized ideas and few take into account the variations depending on period and location. In other words, a man raiding Lindisfarne in 793 would have looked completely different than a resident of Haithabu fighting for his home against Harald Hardrada in 1050. With this in mind, we tend to see a general theme with Viking Age men’s tunics, regardless of location or position in the time scale, however, the tunic from Haithabu tends to put all of these preconceptions on their head. The quintessential “Viking tunic” generally consists of a rectangular body of either a single piece or front and back pieces joined at the shoulders, a simple head hole, trapezoidal sleeves with square gussets underneath for mobility, and elongated trapezoidal gores on the sides. This style of tunic had been in use in one form or another throughout most of Europe for the better part of several hundred years by the dawn of the Viking Age, and continued use in some regions past the end of the era. These details, however, lend credence to the fact that the Haithabu Tunika was far ahead of its time, with an elaborate assortment of gores, in-set, rounded armholes, and even a potential pocket inset into one of the seams. In this article, we will cover the original fragments as they were recovered from Haithabu, as well as the reproduction produced and all details therein. As one would expect from textiles of this age, many are worse for wear, and heavily damaged and worn. This makes our job all the more difficult, as some pieces are nearly indistinguishable as to what they belonged to (such as the supposed “hood” fragment that has caused much debate over recent years). This means that extremely careful study and investigation is key, as any misstep could mean heavy misidentification and eventually a gross misrepresentation of peoples from the period. It is with this in mind that we must combine conventional archaeology with that of reconstructive archaeology, as this can often remedy age-old debates by simple way of rebuilding the original fragment and testing its usefulness in real-world scenarios. The Original Fragments During excavations of the Viking Age Danish settlement of Haithabu (now currently residing in Germany), a vast number of textile fragments were recovered. With expert precision, professional archaeologists such as Inga Hägg managed to piece these fragments together and thus create an idea of what the various garments these pieces belonged to may have looked like. As detailed in her book, “Die Textilfunde aus dem Hafen von Haithabu”, or better known as “Textilfunde aus Haithabu”, we also can have a glimpse into the pieces of clothing from the period and utilize this amazing source of information as our base of knowledge in creating the textile culture from 10th Century Haithabu and Denmark. As stated above, many of the fragments of these suspected tunics are heavily worn, so great discretion must be taken when attempting to identify what they were or where on the body they were worn. Luckily, Ms. Hägg did a lot of this work for us in her book, making this investigation far easier! The most notable fragments we will look at in this article are those of 9, 18, 40, 55A, 72C, and 73. These will also serve as our basis for our reconstructed tunic later in the article. To begin, we will look at fragments 8 and 9. These pieces, though only fragmentary at 32cm long and 10cm wide (fragment 8), lends us less of an idea into the overall look and shape of the tunic, and gives more of an idea of its construction, with some degree of the seams left in place, indicating that rolled-edge hems with a likely overcast stitch were utilized in the making of tunics of this style. Both have been dyed, but what the original colors were is unknown to us. After this has been established as a likely finish for hems, we can begin to look at the overall construction of the tunic itself, starting with fragment 18. This piece measures 39cm high, 15cm wide, and has had its original purpose debated for some time, however, now we do believe it is the remnants of a sort of "princess seam" arrangement on the back of a men's tunic. While Hägg does seem to believe there is a possibility it could also be the front, a rear design makes more sense, especially once the garment has been reconstructed as such. The piece abruptly stops at the bottom, indicating it likely terminated at a seam at the waist, a theory which is supported by other finds such as 55A, 72C, and 73. The piece itself, like all the others mentioned in this article, is made from a medium-fine plain weave wool with a light two-sided felting having been applied. The biggest tell as to the placement of this fragment is that the top has apparently expanded and stretched over its time being worn, ideally made from being worn across the shoulder area. If true, this would indicate an understanding of men's tailoring previously believed to be unknown during this period! This theory is also further built upon by the presence of fragment 40, which also seems to clearly detail a dart used to take in the waist area of a tunic. Next up is fragment 55A, also made from a medium-fine plain weave wool (with the exception of one gore, which is a 2/1 twill) and composed of nine seams in total with five main parts. This is likely the most notable piece of the collection, and gives the tunic its overly unique design, in that it appears to show an array of gores around the lower half of the tunic. Unlike other regions’ designs that bore a far simpler array of gores, 55A shows an extremely complex style of fitting, with two trapezoidal “main” pieces, flanked by triangular gores in between, as well as on the sides. The most logical explanation for this is not only fashion, but utility, as this would greatly increase the wearer’s mobility while working or fighting, and allow for a great range of motion, especially if duplicated in the rear, as logic would entail. The location of the top of the fragment appears to show that there was originally the presence of a seam, indicating that the tunic was in a separate upper and lower piece with a seam spanning the waist and joining the two together. The fabric itself is described as "thin and gauzy", likely meaning it was of a finer, softer quality and may have also been worn as an "under-tunic" of sorts. Another interesting feature on this fragment is a small 6cm slit between one of the trapezoidal body pieces and one of the side gores. Initially thought to be a mere rip in the seam, closer inspection showed a separate weave of wool sewn into it, indicating the possible presence of a pocket. This is further supported by the fact that the opening's additional fabric has been folded over twice and then hemmed into the outer fabric using a series of dense stitches. If true, this would be one of the first examples of built-in garment pockets in Europe during this period. The construction of the pocket is unknown to us, as it is no longer present, merely the remnants of its opening sewn to the inside of the tunic. The final two fragments are 72C and 73, both of which appear to show the upper half of a tunic with a full, rounded armhole and head opening. While the hems are largely deteriorated at this point, the shape of the piece still gives us a good idea of where these originally were and their widths. 72C in particular measures 28cm tall and 29cm wide, and shows us the the neckline was wide and well-rounded, which is in stark contrast to the modern misconception that men's tunics of the time had high, keyhole-type necks which were held closed near the throat with a brooch or other device. This also shows us the sleeves and armholes were potentially rounded and inset, further adding to the fitted and tailored aesthetic of the garment. Only the upper corner has a preserved hem or seam, which appears to have been the seam which joined the front and back of the tunic at the shoulder. Fragment 73 is rather identical in nature to that latter piece, though less well-preserved. The fact both pieces appear to be separated near the center of the chest may also indicate that they were part of a garment that had a seam running down the center front, however, studies have shown that when this is taken into account, and we double the width of the piece, the dimensions become rather odd and it is more likely that this is simply where both pieces were torn off when used and repurposed for ship's caulking. It is also theorized that both pieces may simply be the front and back of the same garment. In addition to the previous "primary" fragments mentioned, there are several other, smaller ones, as well. While many of these at first do appear to be inconsequential, they can also offer some interesting insight into just how these tunics may have been developed. One great example of this is fragments 93A & B. Piece A has the remnants of a reddish yarn running parallel to a hemmed edge, and while little remains now, the piece is crossed over by stitches which are yellow in color with the small fragments of a fabric in the same color, which is now believed to be the neckline of a red tunic with yellow trim - a feature which is commonly seen in contemporary artworks, yet is strikingly lacking from the textile record itself! Most all of the seams that are present are of matching construction, showing a clear trend as to the construction of these garments in-period. These techniques generally show a double running stitch, with the excess folded over once or twice (the latter being more common) and then whip-stitched down with a simple, yet dense, vertical hem stitch. This ensures a great deal of stability within the garment and reduces the chances of a seam ripping or “blowing out”, as the presence of these, even after nearly a thousand years, clearly shows! The fact that many of the fragments are lacking all of their seams, yet still bear the shapes of where they once were, leads many archaeologists to believe that these were intentionally cut apart and reused as stuffing for other projects, or even caulking for ships. The Reconstruction Using the above fragments as a guide, painstaking effort was made to assemble the closest possible tunic to those that existed in 10th Century Haithabu as possible. This meant sourcing the most accurate plant-dyed and hand-woven plain weave wool and thread, as well as hours upon hours of planning and patterning to ensure that every feature of this tunic would match up with that of the original fragments. Anything less would result in inconclusive studies as to the tunic’s design and construction. Utilizing and building upon mistakes and inaccuracies with the previous tunic project, we are hoping this is now the most accurate representation of a Type I men's tunic from Haithabu! While dye analyses have been performed, and have determined that most of the fragments were, in fact, dyed, these were widely inconclusive in providing information on what dyestuffs were used, and likewise, what colors the fragments originally were. Since most were used as ship's caulking, and then were subsequently buried for centuries, relying purely on visual study lends little, as well. As such, we opted for a lower-end woad blue in color, to indicate someone with access to imported dyes, yet not enough for something of high enough quality. To begin, the tunic’s main body consists of four pieces; a front and back torso, as well as two “main” lower pieces. In many cases of other tunics from the period, these are all either one long piece, meant to be draped over the shoulders, or two pieces (front and back) at the most. The addition of a waist seam in the Haithabu Tunika appears to be a feature unique to this particular style. According to Hägg, the torso appears to be rather fitted, especially in the chest and shoulders area, with an open, wide head opening and fitted, rounded armholes. The overall shape of the tunic is that of one that has a fitted torso which then billows out at the waist into a full lower skirt. While the front is rather simple in its construction, the back needed to incorporate the "princess seams" present in fragment 18, which takes in the back and adds even further to the fitted and tailored nature of the tunic. The sleeves, like the torso, appear to have been somewhat fitted and bore rounded in-set armholes. While an existing sleeve from Haithabu does exist in fragment 57, it was created from a 2/2 wool twill and likely did not belong from the same garment as the plain weave fragments, meaning we had to use other knowledge of designs at the time for the reconstructed sleeves. We do know the armholes were set-in and rounded, meaning the sleeves were likely quite fitted, and also likely had a seam running down the back of the arm, rather than underneath it. As such, this is the style we opted for on our reconstruction. The torso is then separated from the lower half of the body via a seam at the waist. This consists of two “main” lower pieces (four in total, two in front, two in rear). The lower pieces are flanked by triangular gores, both on the sides, as well as in the center front and back, making a total of six gores around the lower circumference. This adds an extremely large amount of excess material, even when scaled to the original fragments’ measurements. The reasoning for this could be twofold; both function, as well as fashion. As function would mandate, the excess material around the bottom would allow for a great deal of movement, both in work as well as combat, and keep the wearer from becoming bound in his fitted tunic. We see similar designs on later tunics which seem to have this geared more toward function, as well. The second theory is fashion itself. As other finds have shown, people of the Viking Age were also privy to the same fashionable vices as we are today, as is noted by certain tunic, trouser and accessory finds, so a tunic of this style would likely not be much different. We have few written accounts on Viking Age Danish fashion trends, though even depictions of the Normans, Viking descendants, on the Bayeaux Tapestry show a very similar tunic style, with a fitted torso, and massive amount of fabric in the lower half, often worn in what appears to be a bunched and pleated manner. We have a few accounts that seem to allude to the fact that many early Norman trends followed those of the Danes (such as a reference to Normans sporting “Danish-style hair fashions”), so again, it stands to reason that both a pictorial example, as well as an original find can come together to paint a rather conclusive picture of that fashions of the period. Though initially written off as a mere seam rip, further analysis showed that a small, previously ignored, gap between the seam about halfway down on one side between the main lower piece and a side gore could have potentially been a pocket. This seam appears to have fragments of another wool textile sewn into them, meaning something was sewn here at one point. Since any sort of mending or repair is unlikely here (the seam would have been simply stitched back together), Hägg believes this could have been a potential pocket. If true, this would be one of the first examples of a built-in pocket on an Iron or Viking age garment! Since the pocket has long since deteriorated, or reproduction is somewhat conjectural, and was constructed in a rather primitive fashion, with a single piece of un-dyed wool folded over and sewn to the inside of the seam with the top and bottom sewn up to close it in a rectangular shape. The tunic’s overall fit and wear leaves much to be desired by today’s standards, however, for the period, it would have been a top-of-the-line garment. Between the array of gussets for mobility and fashion, the in-set sleeves (an innovation of the time), and the addition of a potential pocket, this tunic would have most likely been heavily desired by most of the male citizenry of Haithabu. The fitted torso and in-set sleeves do seem to hamper movement to some degree in the arms and shoulders, however, the wide, open neckline provides ample breathing room and does not bind up around the neck when working or fighting.

In Conclusion To conclude, it must always be noted that this results are by no means conclusive, and should always be taken with a great degree of skepticism. Since this is a fashion item from well near 1000 years ago, we will perhaps never truly know the entirety of how it was made or worn, or the exact societal role its wear played, however, we can assess from the few existing sources and finds to try and paint a picture as close to the real thing as possible. Studying the remains of these garments and reconstructing them is a very beneficial way to determine whether certain fragments are what they appear to be, as this can sometimes show through reproduction that what was initially believed to be one part of something, may be completely wrong when practically applied and a revision is needed. These reconstructions also serve as a great benefit to study the actual manner in which these items were worn, as well, as certain features may only allow certain fashion trends to be reflected (such as the great amount of fabric that must be pleated and gathered around the lower half of the subject of this article). To merely study the fragments of a garment is rarely a complete assessment, and only through thorough reproduction and wear can we start to see a semi-clear picture of how it might have been worn and the role it played in society. New sources are always welcome and are constantly being searched for so that any additions or revisions can be made, so this article (and field in general) are ever-evolving and changing. Photo & Information Sources

Cristian Alejandro Botozis

2/13/2020 03:15:19 pm

Your job is fantastic, congrats! where i can find a pattern abot this kind of tunic? Thanks in advance Comments are closed.

|

AboutThis part of the site will look at the various aspects of life on Viking Age Danish people. From what they ate, to how they may have fought. Archives

July 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed