|

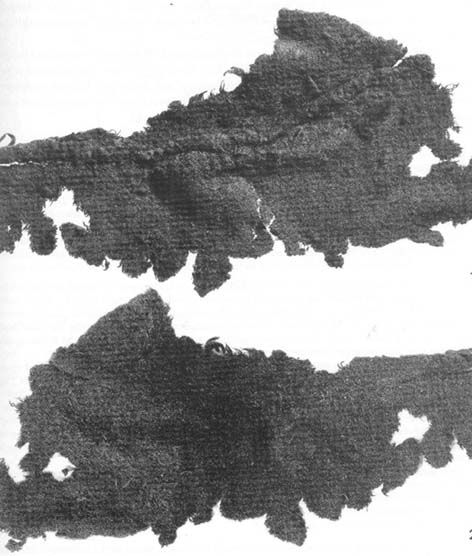

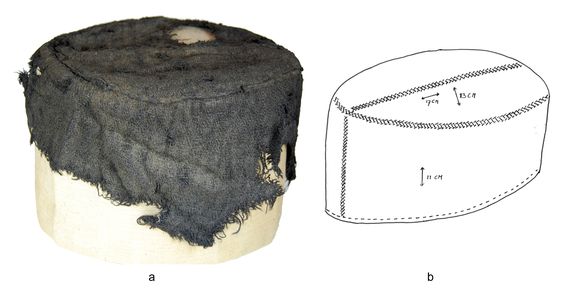

Location: Haithabu, Current-Day Germany & Leens, Netherlands Date: Approx. Late 10th Century Culture: Late Viking Age Danish Estimated Social Class: Unknown Garment Type: Hat To date, no complete hats have been recovered from the harbor at Haithabu, so much of what we have to go from is conjecture and a good deal of reconstructive archaeology. Although no complete find has been recovered (nor are the forms of headwear worn by Viking Age Danes mentioned in any of the literary works from the time), we can still assume that in Haithabu’s 200+ year run that many hats – and many styles of hats – were probably worn. So what style of hats were probably worn? In short, the most probable was that of a pillbox design such as those worn by the Romans, and later, by the Carolingians in what is now the Netherlands and central Europe. This article will focus primarily on this style of hat, as the most evidence for its use exists when compared to other styles from the period. To start, a pillbox hat is a hat with a flat top (made from one or two pieces) and rounded sides, which means, as its namesake implies, it comes in a pillbox shape. What the Viking Age Danes called the hat is unknown to us, or if the hat even had a separate name and wouldn’t have been referred to as nothing more than a “hat,” with nothing to denote a specific style. As stated above, few, if any, literary sources from the time refer to the headgear worn by Danes during this period, so those are unfortunately not of much use when determining a proper name for the hat, and as such, the term “pillbox hat” will be used for the duration of this article. So why is this style the most probable candidate to have been worn in Viking Age Haithabu? The answers are numerous. The first and foremost being the textile fragment recovered from Haithabu. The fragment, catalogued as piece S35, was recovered is what is believed to have been the upper sections of a well, and was most likely disposed of once it because too worn to continue use. It is thought to date to around the late 9th Century and is made from a 2/2 wool twill. The piece itself is rather ambiguous, being merely two pieces of wool textile sewn together with a seam down the middle. To many experts, however, the shape of the seam, and the fact that the piece appears to have been heavily worn, indicates that it most likely fits the shape of that of a pillbox hat design. When one compares the fragment’s shape to that of a reconstructed pillbox, the resemblance is uncanny. Despite the piece dating to the 9th Century, the style itself very well could have continued its use well through the fall of Haithabu in the early 11th, as this type of hat had already been in use since at least the 3rd Century (perhaps even earlier), and saw use well into the Renaissance. The second reason is the near-complete find from the Netherlands and its proximity to Haithabu and Denmark. The hat in question, numbered as find b1930/12.34/1, was recovered from Leens, Netherlands and is a near-complete extant find. It was constructed from diamond twill wool and is made from three pieces, two for the top and one that goes around the main body, and is a textbook example of a pillbox design. So why would a hat from the Netherlands be grounds for one to present it as an example of those worn in Denmark? The answer is simple: Location and commerce. We know this particular style of hat was a rather prolific design, after all, it began its life as a Roman design and lasted well into the Medieval Period and Renaissance, and was used all throughout Europe during its lifespan. The close proximity of the Netherlands, and Carolingian Dynasty as a whole, to Viking Age Denmark is also a good indicator. While the two factions had rather off-and-on relations during this period, with some areas (primarily East Francia) even being under Danish rule during the latter part of the 9th Century, when the fragment from Haithabu is believed to have been dated to, there certainly were periods where the hat could have been introduced to the Danes of the area via Carolingian influences, be it through trade and commerce, or war and occupation, that exposed the men fighting, settling, and trading to new fashions of their enemies and beneficiaries. The location and probability for trade and exposure between the two groups, coupled with the seemingly perfectly-shaped fragment from Haithabu itself seems to begin to paint a very convincing picture for this style to have been worn. The presence of items adopted through trade and/or war and occupation by Viking Age Scandinavians in gravesites and other areas of note, such as the ring uncovered in Sweden bearing Islamic inscriptions, indicates these peoples were more than willing to adopt fashions from their neighbors, business partners, and subjugated masses. What about other styles? While it is a fairly good reality that other hat styles were in use during this period of Danish history, no examples, be it literary or physical extant finds, have been found, at least where Haithabu and Denmark are concerned. We do have examples of other hats in use in other regions of Scandinavia during the Viking Age, such as the conical hat found in various sources (not least of which, the famous Icelandic bronze Thor figurine), though again, an argument for their use in Denmark is not as great as the pillbox simply due to a lack of physical evidence from the area. Paneled hats, such as those from Sweden and Moschevaya Balka, are also ambiguous options for potential styles worn in Denmark during this period due to a lack of evidence. The frequency of which hats were worn during this period is also likely unknown to us. While some artistic sources, such as the painting of Viking raiders housed in the Scandinavian School in Oslo, Norway, show nearly all the men involved wearing hats, we must also take note that sources such as this were certainly post-Viking Age and do not accurately portray the men or equipment of the time, but are probably rather an artist’s interpretation of how he thought they may have looked. One could argue that the lack of extant archaeological finds regarding hats is an indication of their rarity in-period, however, I personally do not buy this notion. There are just as few complete tunic finds from the period, so by this logic, does that mean tunics were a rarity? Hardly. Perhaps we will never truly have a complete picture on just how common hats were worn, or what myriad of fashions were in use during the Viking Age in Denmark. Photo Credit:

Comments are closed.

|

AboutThis part of the site will look at the various aspects of life on Viking Age Danish people. From what they ate, to how they may have fought. Archives

July 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed